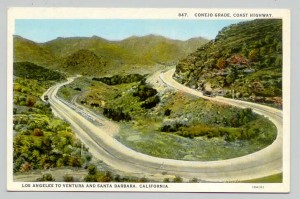

One of the books I picked up on the bookstore tour was Cattle on the Conejo, by J.H. Russell. It is a collection of reminiscences by a rancher who had been on the property since his birth in 1883. That property was the Triunfo Ranch, the eastern edge of the larger Conejo grant. For those who don’t know, Conejo Grade straddles the Ventura/Los Angeles County line and is the passage on Highway 101 between Thousand Oaks and Camarillo.

What attracted me about the book was a short section on building the first state highway in California which was routed over Conejo Grade. I have to go back and look at my notes, but this roughly around 1910-12. El Camino Real boosters claim that the original state highway (Highway 2) followed the historic El Camino Real, at least through Southern California. That would mean the historic El Camino Real passed over Conejo Grade.

Of course, there was no historic El Camino Real, at least not one that dates any further back than 1891. And though the Camino Real Association holds that the route of the highway conforms to the fictional historic road, the truth is that the fiction bent to the modern reality. More about that below.

But for now the question remains: why did the engineers decide to build Route 2 over the Conejo Grade? From state highway documents I’ve read, it seems clear that engineers, being engineers, built the roads in the most practical places they could without regard to scenery, history, pressure from local governments and business, and certainly not to preserve any sense of history. The designers of the national system of highways and the Interstates followed the same bloodless number-crunching approach as the California engineers, a process well-documented in Earl Swift’s The Big Roads: The Untold Story of the Engineers, Visionaries, and Trailblazers Who Created the American Superhighways.

What were the criteria that made these engineers choose Conejo Grade? Convenience. Traveling from south to north in coastal Southern California, the path of least resistance out of the Los Angeles basin is over Cahuenga Pass into the San Fernando Valley. But once in the Valley, the dilemma is which way to get out again. San Fernando Valley is walled in by the Santa Monica, Santa Susanna, Simi, and San Gabriel mountains. There are three possible passages north: west through Calabasas and over Conejo Grade to Ventura County; northwest through Chatsworth and over Santa Susanna Pass into Simi Valley; and north through the Fremont Cut into the Santa Clarita Valley, then west along the Santa Clara River (Highway 128) to Ventura. These three passes out of the Valley are currently used by the 101, the 118, and the 5, respectively.

According to Russell in Cattle on the Conejo, the highway engineers were planning to go over either Conejo Grade or Santa Susanna Pass. Conejo was the first passage used by stagecoaches; Santa Susanna wasn’t usable as a stagecoach route until a passage was blasted out of the rocks (All of this information courtesy of Outland, Stagecoaching on El Camino Real). And the Fremont Cut was, even in 1910, still uncomfortably steep even for a car (Taussig, Retracing the Pioneers, stating that the Fremont Cut was the steepest road they travelled in their six week jaunt from San Francisco to New York). How did they choose between Conejo and Santa Susanna?

“There were two proposed routes leading north out of Los Angeles, one through the Conejo and the other, farther inland, through the Simi Valley. We eventually heard that it was settled definitely that the route would be through the Conejo. Almost immediately, however, I learned from a man who was on the routing committee that there was renewed agitation to have it go through the Simi Valley, so it would be well for the Conejo and Oxnard people to meet with the Highway Commission when the Simi people did. The greatest drawback to the Conejo route was the lack of a railroad to get the gravel for concrete on the job. The Simi people stressed this point heavily. Finally I said, “We have a creek with lots of gravel on the Conejo and it would be easy to get if it is suitable.” Then I added, “Commissioner, we have no railroad and we need an all-year road. If I can get you a signed agreement by the property owners from Calabasas to the top of Conejo Grade that they will deed you the land for a right of way wherever you want it, would that help?” He answered, “If the gravel proves suitable for road and you can get the rights of way, I think you will get the road.” The gravel was suitable and all but two landowners agreed to give the right of way, so the road came through the Conejo.”

Cattle on the Conejo, pp. 68-69.

So Russell essentially did a good part of the engineers’ groundwork, so to speak, for them. I think there is something very reassuring about that story. It sounds like bluster, but it’s just practical enough to be true. Someday I hope to research the issue from the Highway Commission side and see what they say, if anything.

But as long as we’re on the issue of Conejo, is there any legitimacy in the claim that Conejo Grade is on the mythological Camino Real? According to Bancroft, the first Portola expedition left the San Fernando Valley northbound over the Fremont Cut (though Fremont hadn’t made the cut yet, of course) and down the Santa Clara River to Ventura. On the return (southbound) trip, they entered the San Fernando Valley from the northwest via Simi Valley over the Santa Susanna Pass. Russell continues to state that as of the mid-1950s, “Highway 101 from Cahuenga Pass to Calabasas, the original El Camino Real, is in substantially the same place it has been for at least sixty years. From Calabasas to the Conejo Grade, however, very little is on the same right of way as the original county road or the first state highway.” But I think Russell is referring to El Camino Real as declared by the Camino Real Association; in other words, the first state road over Conejo Grade. I would have said “paved,” but I’m not sure when it was paved. Undoubtedly, later expeditions used the Conejo Grade. And as I noted earlier, it was apparently the easiest grade to make a passable road over. But I think it is at least clear that the State Highway was not built to commemorate El Camino Real, at least along this stretch.