“The shepherds, the herdsmen, the maids, the babies, the dogs, the poultry, all loved the sight of Ramona.”

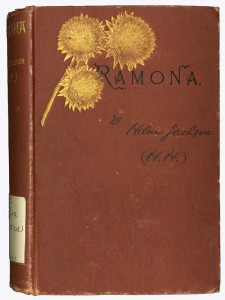

I recently read Ramona, the 1884 novel by Helen Hunt Jackson that launched a thousand suburbs. The book was instantly popular, and reportedly has never been out of print. Ramona is the reason so many people traveled to California in the 1880s. They came to see the locations mentioned in the book. Once they were here, well . . . who could go back to Iowa once you’ve spent a winter in Southern California? The 1880s saw a land boom in So Cal, and Ramona was the means by which land promoters lured people out here. That, and a savage train rate war that brought the price of tickets from from to the Mississippi to California from $125 to $15, and even as low as $1 for a time.

I really wanted to hate the book. Dreaded reading it. Put off starting it because it seemed like it would be a chore. But I had to read it for two reasons. First, Ramona is the primary source of Mission Revivalism in late-19th century California. It is the reason the missions were rebuilt, and El Camino Real reclaimed, and, I suspect, why every year Fourth Graders all over California still have to build a mission model. Second, this upcoming week I am staying near Santa Paula, which is down the road from the primary geographic site associated with Ramona, Rancho Camulos. (In fact, Rancho Camulos still bills itself as the “Home of Ramona” and runs a “Ramona Days” event every year.) I have arranged a special tour for family members, and it seemed to me I should at least have the courtesy to have read the book first.

But I have to say that I ended up getting pulled into the novel, and but for some poorly drafted passages (see above), and the usual 19th century purple prose, I actually enjoyed it.

And no wonder. If it were a movie, Ramona would be billed as Romeo and Juliet in the Garden of Eden. It combines the time-tested tropes of star-crossed lovers and the fall from grace. In this case, Romeo is Alessandro, son of a wise Indian chief and a model Nobel Savage; Eve is Ramona, blue-eyed, half-Indian maiden beloved of all, including poultry; the Garden of Eden is Rancho Moreno, one of the last of the great Ranchos, run under the iron grip of the quietly domineering hand of Señora Moreno, widow of one of the Mexican land grantees, and one of the dying breed of Californios. The fall from grace and expulsion from Eden comes when Ramona, raised to be Gente de Razon, wants to marry Alessandro, who, despite his good looks, is Indian, and thus Gente sin Razon, a person without reason. To the proud Señora Moreno, that makes him untouchable. You can read a decent summary here.

The book, as mentioned above, was hugely successful. It’s been made into a movie four times )the first Ramona was Mary Pickford); staged annually since the 1920s (with only a few years break during WWII) as an outdoor play in Hemet, California (with Raquel Welch, née Tejada, in the starring role in 1959); and most recently as a Telenova (around 2000). All of which an author normally thinks of as good things.

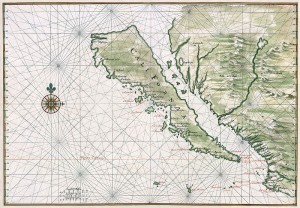

But in this case, Ms. Jackson, considered her book a failure. She set out to write the book in order to draw attention to the plight of Native Americans in California: an Uncle Tom’s Cabin for Native Americans. But in doing so, she inadvertently created an idealized pastoral, pre-American culture of the leisure of rancho life of the Gente de Razon, and gave it the extra touch of pathos that disappearing cultures evoke. Her descriptions of life on the veranda )claimed to be modeled on the south veranda of Rancho Camulos), surrounded by citrus groves, the warm, languorous winters set against the backdrop of decaying mission ruins, all blessed by loving, paternal padres overpowered the social message that is just as carefully drawn. She created the myth of California that those of us who grew up here all share, what Carey McWilliams called our “Spanish Fantasy Past.”

And since then, Southern California has never been the same.